Not only is #112 on the List of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die, “Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury, still pertinent because of all the bozos out there who are trying to ban books in 2024 (or, worse, treating the dystopian classic as a how-to guide), but also because there’s an undercurrent in America that seems hell bent on bringing the spirit of this nightmare to fruition.

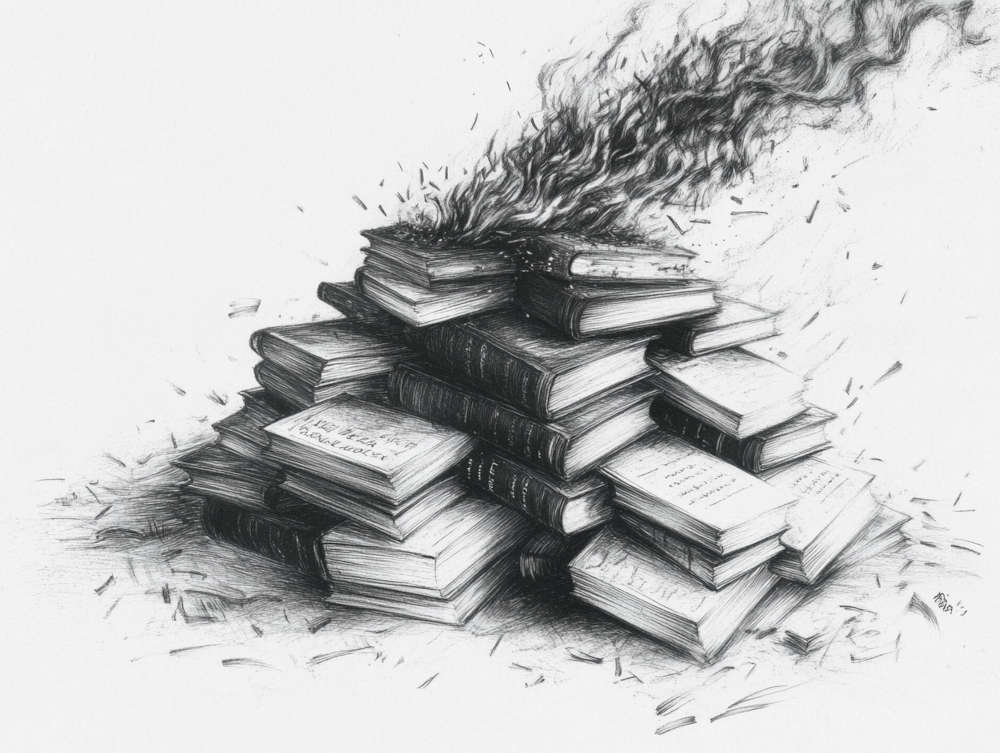

A lot of people know that “Fahrenheit 451” is about burning books, but they think the novel stops there. “The bad guys don’t want anyone to read books so they go around burning every book they can find.” This is true, and I think the message has spread — people who physically burn books they don’t like are thought of as insane, they are ostracized, shunned. Which is fine; like I said, they’re bozos. But the pleasure of burning isn’t the actual problem.

The problem is that people find ways to get rid of books, to take them out of the hands of people who need them most. Why? Because ignorant people are easier to exploit.

To sprinkle a little Rage Against the Machine into the mix: “They don’t gotta burn the books, they just remove them.” Burn a book and you’re a fascist, but, for whatever reason, convince millions of people that books aren’t important and nobody bats an eye.

The real message of Fahrenheit isn’t that we need to coat books in asbestos — the threat in Bradbury’s work isn’t as much a flamethrower as it is the presence of an anti-intellectual movement that has been growing like a dumb weed in the ditches of middle America.

Books are representative of knowledge. They are the virus that causes the disease of not-being-a-moron, they give rise to questions and oblige us to right the wrongs of the past. Anti-intellectuals, though, call that “unrest,” and they’ve convinced so many people to find pride in never having cracked a book.

Who are these anti-intellectuals? The U.S. is rife with them and they’re often in the news:

They are people who, when confronted with a worldwide pandemic, get mad at doctors who tell them to get vaccinated and/or wear a mask.

People who, after seeing the disastrous effects of climate change, send death threats to meteorologists.

People who, after wave upon wave of school shooting, don’t listen to any politician who says that maybe we all shouldn’t have access to goddamned assault rifles. (“But then how will we shoot cans of beer in protest of trans people?!?”)

“Fahrenheit 451” is about a man, Guy Montag, who goes woke. Or, as Elon Musk would put it, he gets infected by the “woke mind virus.” (If any of that just made you vomit in your mouth, just know that you aren’t alone, and be sure to take the time to brush and floss. If you don’t know I’m talking about: Here’s two idiots chatting about it. Note how the oligarch currently trying to buy votes in Pennsylvania talks about how “moderate” he is.)

A fireman by trade (a person who does the book-burning in this context), Montag meets a free-thinking youngster when he’s walking home one night and commits the egregious sin of becoming curious, which, a few people might recognize, is the first step down the slippery slope of learning. Montag begins to wonder why they burn books — what’s in them that’s so terrible? Does anyone know?

After he watches a woman get burned alive with her book collection, things start to spiral. He takes a few books home, he flaunts them in front of his wife and her friends. He starts questioning things. A robot dog sniffs around his door — a sure sign of trouble! Montag feels like he needs to do something.

But Montag doesn’t really know what he’s supposed to do. Once you realize that your whole society is based on a series of fallacies, what can one man do to fight it? Print more books? Run away? Actually fight back by planting books in the houses of firemen and then reporting them so they get arrested?

Montag doesn’t have the answers; nobody does, not in the novel, nor in our actual world of “Fahrenheit 74” (which is so named for the temperature at which assholes turn on their air conditioners).

Montag makes a series of rather bumbling mistakes (but they’re the “right” mistakes) and ends up getting found out (his wife turns him in) and running for his life before he encounters a bunch of other intellectuals who are on the run from Project 2025 … er, I mean, this nameless dystopian government that bears no resemblance to any current trends in American politics.

These roving intellectuals have each memorized a book and essentially serve as a walking library, hoping only to survive long enough to ensure that the knowledge they keep can be passed on and, maybe, be of use to the future. Because certainly, certainly this government can’t last.

(It can’t. Shortly after Montag goes on the run, his whole city is blown up in one of the wars that seem to start every day.)

It’s a bleak ending, but looking at the world today, one can’t help but feel that bleakness is the zeitgeist.

Because all those people who would have been burning books if they were fictional characters have realized that it’s much easier to convince people that they don’t want to or shouldn’t read books. It is astounding to me the number of students (and adults) who proudly proclaim that they don’t read, that they haven’t read a book since sixth grade. They say it as if they’ve cracked a code, or pulled the wool over someone’s eyes.

“Those wily teachers tried to fool me, but I got around them — I just had ChatGPT summarize the whole book for me while I watched YouTube shorts. Checkmate, atheists!”

One thing that I don’t believe was true when Fahrenheit came out (1953) but is certainly true today is that reading is considered work. The news I keep hearing from university professors is that more and more students are coming to English departments across the country unable to read books.

When I studied English, ages ago in the early 2000’s, I took any number of literature classes that would assign one book a week. Now, though, that amount of reading is impossible for many incoming university students. Is it an attention span issue? Are public schools failing us? Are parents and their “just give ’em an iPad” mentalities to blame?

A little of all of them, I’m sure. One thing is for certain: A whole wealth of knowledge, tremendous variety of perspective, and just general fun is being placed out of students’ reach — and all without the use of kerosene or matches!

Similar to Guy Montag at the end of “Fahrenheit 451,” I sometimes feel that we English teachers are wandering through the wastes of tomorrow, carrying information and skills that we hope will someday be valuable again.

Last week, I took an informal poll of my approximately 220 students, asking how many of them had heard of Mark Twain. You know, the author. All told, about 15 of them knew who I was talking about.

“Wait, really?” I asked. “You don’t know Huckleberry Finn? Tom Sawyer?”

I was met with a sea of blank faces.

And in the distance, thunder.