I’ve never understood the idiom, “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” Book covers have a lot of useful information on them: there’s a synopsis, author information, maybe some helpful photos that’ll key you into the genre — one of the fundamental goals of a book cover is to help you judge whether or not you want to read that book.

The gist of the saying is that what’s inside matters more than what’s on the outside, but you can’t dismiss the elements of a book that aren’t related to its words. You’ve got to think about the whole package, including the cover.

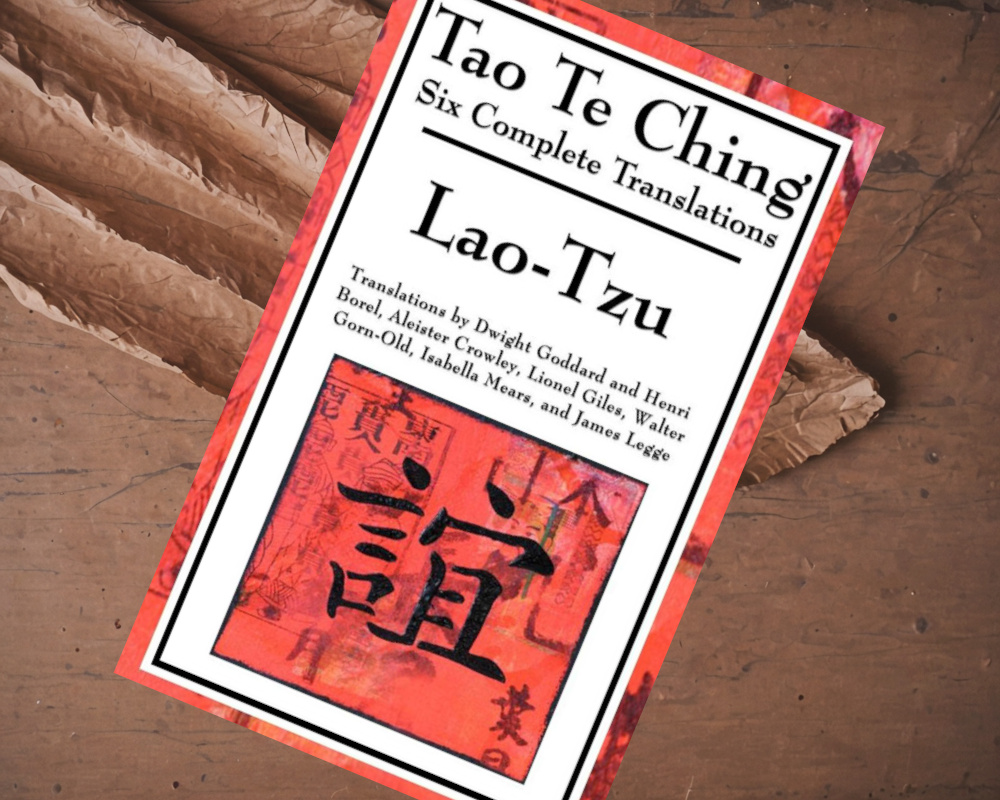

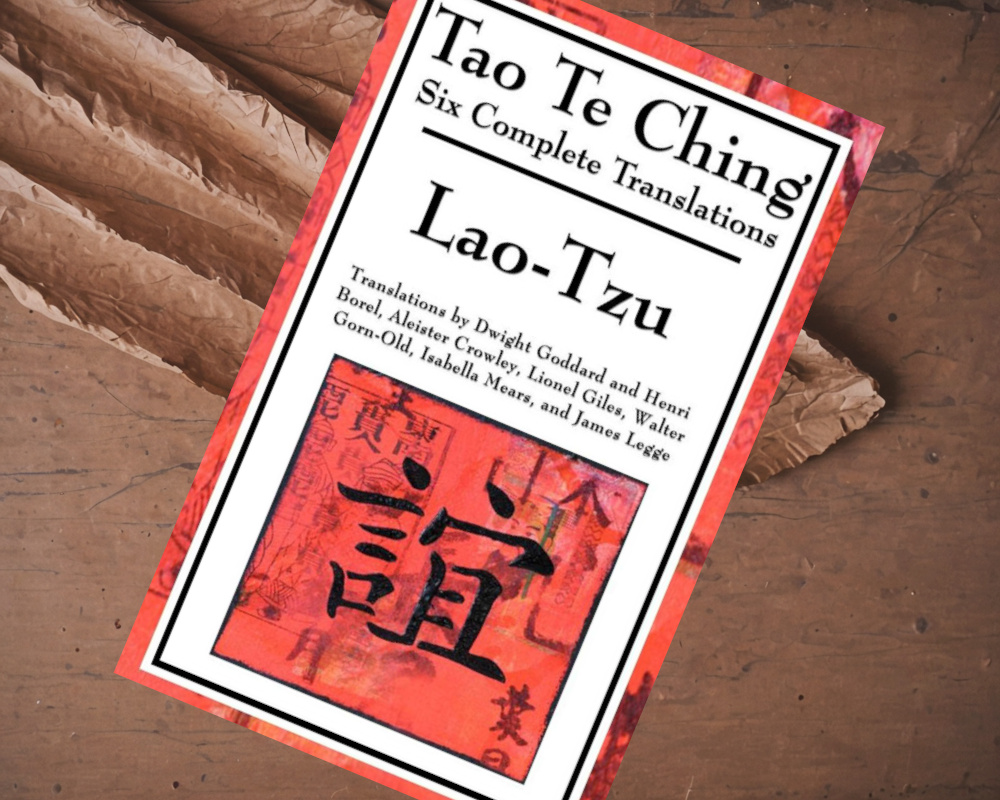

When I was picking out the copy of “Tao Te Ching” by Lao Tsu (#30 on the list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die) that I was going to use, one of my primary concerns was the way the book felt. It had to be something that felt good in my hand, something sturdy with a little bit of give to it, something elegant and yet robust. There’s no easy way to describe the way a good book feels when you hold it, but you know the feeling when it strikes you.

At Barnes & Noble (the only local bookstore that had any copies of Tao), I was able to find four or five different editions. They were all slim — the book is not long — and had a variety of covers and weights of paper. Some were flimsy, some were sturdy. Some were glossy, some were matte. I collected them all and took the small stack of books to the Starbucks in the back of the store, ordered a latte, and sat down to inspect each one.

Knowing others is intelligence;

knowing yourself is true wisdom.

Mastering others is strength;

Mastering yourself is true power.

― Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

I felt silly doing so. There’s something inherently funny about a middle-class white guy getting into an ancient Chinese philosophy, and there’s something ironic about doing so in a corporate coffee shop in the back of a corporate bookstore. That didn’t bother me, though. You’ve got to find silly, frivolous things to do with your time. Things that would baffle an outside observer, things that you can’t account for. A certain percentage of your life ought to be spent on a figurative trampoline, bouncing pointlessly for the sheer enjoyment of the act. In my case, I like to sit down in coffee shops and read translations of books whose first lines essentially tell you that you won’t understand what you’re reading.

Flipping through each of the editions of the “Tao Te Ching,” I noticed there were some fairly stark differences in their translation. This is not only because the text was originally written in 2,500 year-old Classical Chinese, but because many of the phrases and ideas don’t have one-to-one English equivalents. “Tao” is typically translated as way or path, even though the actual word is something more ephemeral, but every book had stark differences on a line-by-line basis. Were they accurate? Did the meaning change based on who had translated that particular text?

I read a lot of translated works and have thought about this question frequently, ultimately deciding that it doesn’t matter one bit. One can never know — it’s best just to judge the translation on its own merits and don’t fall into the rabbit hole of, “Was this correctly translated?” Meaning is lost in translation, but new meaning is also constructed, and (short of mastering both languages) you’ll never understand how.

The text upon which I settled was a small paperback edition with a black cover featuring a rocky outcropping in front of a foggy forest scene. I picked it because I liked its wording of the first chapter, and also because the paper was the right weight. It was the kind of book I could see myself annotating with a pen in the early morning when I was taking a train to work, underlining passages that I would ponder while looking at the countryside speeding by.

(I should point out that this image only exists in my mind. In Nebraska, trains haul corn or coal and little else. There are maybe a handful of passenger trains in this state, but they are kept more for novelty than practicality.)

Each of the chapters of the “Tao Te Ching” reads like an instructional poem, as if part of a poetry collection meant to teach you how to live a life of virtue. (This, in fact, is not far from how it was originally used.) The meanings of the poems, however, are quite elusive.

Here’s how it starts:

ONE

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

If that seems confusing, don’t worry — you’re not alone in your confusion. It’s meant to be confounding. The first line points out that you can’t express the Tao (“way”) in words. In a certain sense, it’s saying that you won’t learn about the Tao by reading a book. You can only live the Tao; it’s an experience, not words.

My reading of the “Tao Te Ching” was not a quick one. I’d been feeling pretty overwhelmed with the amount of work I had taken on over the past few months, so I’d decided to incorporate a little bit of meditation into my daily routine. Nothing too fancy or time-consuming; I meditated each morning for perhaps ten or fifteen minutes. Was it helpful? I think so. I’ve gotten better at noticing times when I’m feeling anxious and have been able to ground myself. Reading the “Tao Te Ching” was a part of this practice, and I’d read a few chapters every day before work.

I also visited websites that offered interpretation of the Tao. While I would read each chapter and try to form my own understanding, it was helpful to be given some context. This website, I thought, was one of the most useful, offering chapter-by-chapter analysis and a clear “reading” of each section.

I also listened to a Taoist podcast called, “What’s This Tao All About?” Mostly, I listened to it while walking home from work or taking strolls through my neighborhood.

While I was walking, a troubling thought entered my mind.

Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.

― Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching

I was worried that the whole thing was a scam. There are a lot of “self-help” philosophies out there that try to sell you on the idea that there’s something wrong with you and reading a book can fix it. While I don’t believe that Lao Tsu is a 2,500 year-old shyster, it isn’t outside the realm of possibility that his philosophy has been co-opted by people who just want to sell books and videos and online subscriptions.

People who are looking for some sort of spiritual awakening are often vulnerable, and vulnerable people are easy to take advantage of. So are travelers, and you’ve got to watch out for fraudsters the same way you’d watch out for bears if you went hiking in the wilds of Wyoming.

Years ago, when I was backpacking through Cambodia, I had a similar feeling — a feeling that I was about to get scammed. My friend and I had just arrived in Siem Reap on a bus from the Vietnamese border, and it had been a horrible ride; passengers were tucked into seats like Tetris pieces, our legs jammed against the seats in front of us, our bags stored practically on top of us.

When the doors of the bus opened, we tumbled out of the vehicle and the driver shouted, “Jenga!” My friend and I did our best to stretch away the soreness while we looked around this new city.

While it isn’t always the case, you can generally tell how wealthy a country is by how clean its streets are. Only wealthy parts of the world bother to keep gutters clean; poor countries don’t hire cleaners to look after something as frivolous as the side of a road — they need that money for more important matters. By that rubric, Cambodia was not a wealthy place. The streets were lined with red dust and garbage, greasy and unkempt. We were dropped off in a parking lot on the side of a highway, and it was filled with tuk tuk drivers who were calling out to us. By name.

“Toad, hey!” they called. “Toad, you need a ride!” They weren’t asking.

We were quick to realize that the company through which we’d purchased bus tickets had likely called ahead to let others know the names of the passengers who would be arriving. The tuk tuk guys were trying to sell us rides, hoping that their use of our names would oblige use to ride with them. It was a tactic that preyed upon travelers who were insecure, unsure of how to proceed once they’d arrived.

While I was angry about it, this is just something that happens when you travel. People will take advantage of you in small ways, trying to sell you kitschy garbage, overcharging you at restaurants, leading you into obvious tourist traps where “art students” try to sell you paintings. In the worst cases, they will try to steal from you or (very, very rarely) abduct you. It’s something that you just have to accept, something that you have to prepare for and be wary of.

In our case, we did end up taking a ride on one of the predatory tuk tuks. The bumpy trip was only about $8, and it saved us having to walk two miles to our hostel.

Plus — and this is important — we were relatively wealthy people and the locals treat you well if you play along. Siem Reap is a tourist town; a lot of people there make their living selling tuk tuk rides, food, and drinks. There’s no use in angering a bunch of people who only want a few bucks.

While I had the sense that Taoism (or pseudo-Taoism) could be somewhat scammy, the tell-tale sign of a scam never seemed to materialize. In other words, there never came a point when anyone asked me for my credit card number. Sure, the podcasts I listened to asked for donations, but most small-scale podcasts do that. And the websites that are about Taoism all look like they were optimized for Netscape Navigator and certainly don’t ask you to subscribe.

The Taoist teachings you find in the “Tao Te Ching” are fairly difficult to parse. They all read like poetic parables that focus on juxtaposition and contradiction — paradoxical elements abound, and the overall message is about quitting the struggle. You’re advised to be like water, not to resist, not to seek wealth. Just be.

When you are content to be simply yourself and don’t compare or compete, everyone will respect you.

― Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

Tomorrow is going to happen whether you break your back trying or not, so what’s the use in breaking your back? Things will work themselves out; they have throughout all of history.

“They’re basically advocating for laziness,” I told Sarah. “‘Action through inaction,’ that sort of thing.”

“I can get behind that,” Sarah said.

“I mean…yeah. There is something satisfying about a philosophy that tells you not to worry so much and not to constantly try to improve.” Or, at least, after a semester of extremely hard work, it feels good to have a philosophy that tells you to take a break.

Hence it is said:

The bright path seems dim;

Going forward seems like retreat;

The easy way seems hard;

The highest Virtue seems empty

― Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

All of this, though, is completely at odds with the way most Americans live their lives. We are an awful bunch of try-hards, each of us hell-bent on “self-improvement.” Even as I read about Taoism, I constantly thought about how I could use this to become a better person. I pictured myself with a shaved head, perhaps wearing robes, perhaps walking through a jungle or a rock garden. I’d be a whole new man, a man to whom stress was a forgotten dream.

That won’t happen, of course. Even if I wanted to change, to become a full-fledged Taoist, I think the community I live in is fundamentally opposed to the transformation. It’d be like an ice cube spontaneously forming in the middle of a hot tub — theoretically possible, but utterly unlikely.

Still, there’s a side of me that longs for it. It’s the same side of me that will occasionally listen to a lecture by Alan Watts and dream of becoming a monk. One of those ascetics in wilds of Tibet, or perhaps Japan, who do walking meditation and only eat what people give them. I wonder if those kinds of monks are allowed to read books. They probably don’t get to go to Barnes & Noble, but there certainly can’t be teachings that go against libraries.

When those monks pick out what they’re going to read, do you suppose they consider the cover of the book they’re holding? The weight of the paper? The flexibility of the spine? Perhaps they’ve transcended all that to live on a spiritual plane that precludes such judgements. Paper is paper, and words are words. Trying to find books you enjoy is just needless struggle.

Or, more likely, they simply don’t worry about such things.

(I just looked it up and, yes, monks of both Buddhist and Taoist flavors can go to the libraries. It depends upon the sect, but many/most of them value education and don’t prohibit reading for pleasure.)