How Books Are Like Drugs

We might not have concrete proof for the gateway hypothesis when it comes to drugs—does early use of cigarettes and alcohol lead to later use of harder drugs like cocaine or heroin?—but I’m convinced the gateway hypothesis holds true for books. Starting to read at a young age seems to encourage a lifelong love of reading, which is something I think we can all agree is good.

While I can’t prove it definitively, the anecdotal evidence is compelling. As a teacher, part of my mission is to inspire students to read more, much more, as much as possible — hoping they become so captivated by books that they continue reading throughout their lives. Even if I’m wrong, the worst that can happen is that a few kids are forced to read “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Why Animals?

A question I’ve often wondered: Why do so many children’s books feature animals as the main characters? We can think of countless examples: “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” “Charlotte’s Web,” “The Wind in the Willows,” “Winnie-the-Pooh,” “The Jungle Book,” “The Lion King,” “The Velveteen Rabbit,” “Paddington Bear”—and that’s just in Western literature. People in nearly every culture use animals when they’re writing for children.

It seems there’s a natural instinct among children’s authors to anthropomorphize anything with fur and a cute face.

There are many reasons for this. Animals are relatable and adored by children, and using them allows kids to view their world in new ways. The backyard transforms from a bland patch of grass into a battleground or an adventure zone. One of my biggest regrets about becoming an “adult” is that I’ve lost the ability to get lost in my own imagination the way I used to–to so vividly imagine being a mouse or a cat or a bird navigating through my neighborhood’s secret pathways. In essence, the older I get, the harder it seems to be to play. For children, though, it is as natural as breathing.

Another reason to use animals in children’s literature is that animals are safe. It’s unthinkable to write a children’s story depicting the brutal death of a parent by gun violence, yet Bambi’s mom gets blown away in an absolutely devastating scene and that story is celebrated all over the world–it’s strange if someone hasn’t seen it.

This approach — using animals as characters — lets us explore profound or disturbing themes in a way that’s less likely to traumatize young readers. We can do this while featuring creatures that children find engaging. (Another interesting question is why children find animals like mice and rabbits so fascinating, but that’s a topic for another time.)

The “Watership” Isn’t Actually a Ship

“Watership Down,” number 7 on the list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die, is a book I should have read by now but haven’t. Given that “Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH” is one of my favorites, you’d think “Watership Down” would be right up my alley.

As a kid, though, the title “Watership Down” confused me. I imagined it was something like “Black Hawk Down,” a story about rabbits speeding around the Atlantic in a submarine. How did the rabbits build it? I wondered. Were they welders? And would beavers or ducks lead some kind of rescue operation?

Years later, when a student of mine wrote a report on “Watership Down,” I realized I’d misunderstood the title. A “Down” is simply a grassy hill in southern England, derived from the Old English word “dūn” for “hill.”

The story follows a group of rabbits who leave their warren after a prophetic rabbit named Fiver foresees its destruction. Fiver’s brother, Hazel, believes him, and they set off to find a promised land called “Watership Down.,” taking along any other rabbits who believe them.

While the rabbits in the book do talk, the book portrays them as realistic rabbits with detailed behavior, customs, and even a rudimentary religion centered around a trickster rabbit, El-ahrairah. It’s clear that Richard Adams observed rabbits closely to capture their behavior, probably while walking around grassy southern England, where daily walks are mandated by a government agency.

Challenges & Magic

Watership isn’t magical realism per se, but it does include some inexplicable elements. Fiver’s visions often come true, suggesting he might be some kind of oracle. I can’t tell if this ability is common for rabbits or if Fiver is unique. I mean, if other bunnies had similar abilities, their old warren might have heeded Fiver’s warnings about the humans who began developing the land and killing all their rabbit pals instead of ignoring it.

The bunnies who manage to escape, led by Hazel and the burly Bigwig, face many challenges before realizing they forgot something crucial: female rabbits. Whoops! This oversight leads to a new phase in the story as Hazel and his friends plan to find some girls to ensure their survival. But will the be able to steal some from a nearby warren?

Bloody Rabbits!

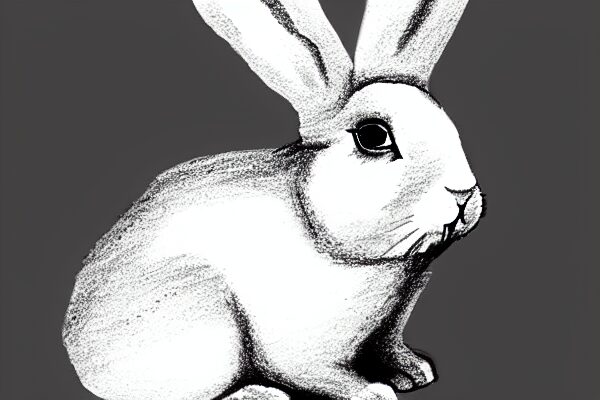

The 1970s movie adaptation of “Watership Down” gained notoriety for its depiction of rabbit deaths. While the book contains violence—reflecting the dangerous lives of rabbits—it’s fairly tame by today’s standards.

Yikes! That trailer makes it sound like a horror story. The book, though, is mostly just rabbits talking and/or running long distances before digging holes to sleep in. Richard Adams could almost be called a naturalist for how much he focuses on nature. The result is rather idyllic prose that makes it easy to forget the occasional snare or dog attack.

The Final Results

“Watership Down” exemplifies why animal stories captivate readers of all ages. By exploring themes like survival, leadership, and resistance through the eyes of rabbits, the book makes complex ideas accessible and safe. Animal stories open new worlds, foster empathy, and, most importantly, encourage students to become lifelong readers.

The sorts of clowns (like me!) who read kids’ books when they’re supposed to be working.

It might not be as addictive as heroin, but whether or not the gateway hypothesis for books can be scientifically proven, stories like “Watership Down” have a special power. They draw us in with lovable animal characters and keep us going with stories that inspire. Perhaps they even spark a lifelong love of reading.

After all, if we can learn life’s lessons from a group of rabbits on an English hill, who knows where else might take us?