With a big enough lens, you can think of all literature as a conversation that people have been having with themselves since Gilgamesh decided to forgo godhood and embrace his humanity. You could probably say the same for art in general, but this is a blog about books, so we’ll skip the cave paintings and focus on writing.

The fact is: Nothing is written in a vacuum. No author is free from influence, and while writers have for centuries sought to create something new and utterly original, what ends up happening is they mash things together or decide to write in ways that are completely counter to the status quo. Either way, everything that has ever been written has been written in response to something else.

Is that pessimistic? Maybe. But knowing that’s the case is what allows us to look back at works of literature and decide what’s important and what isn’t. Generally, we celebrate anything that seems to have taken a substantial step forward or have been influential to others — works of literature that are genre-defining, or that represent a hard swerve to the left when everyone else was going right.

The Big Sleep is Death

This is the mentality that I brought to reading “The Big Sleep,” number 189 on the list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die. Considered a pioneer of hard-boiled detective fiction, one can’t possibly count the number of books/movies that have been influenced by Raymond Chandler’s 1939 pulpy crime novel. Hell, we should consider it a classic if only because The Big Lebowski wouldn’t have happened without it. Never mind The Dresden Files. Or Se7en. Or L.A. Confidential. Or True Detective.

Somebody had to be the first person to think, “I should write a book from the perspective of a poor, drunk private detective with a heart of gold,” and while Chandler wasn’t the first to do so, “The Big Sleep” was one of the most popular works to take on such a character.

And now, nearly 100 years since its first publication, the gritty detective novel is still hugely popular. Does the modern version need twists, like having that detective be a wizard who fights gods on or around Lake Michigan? Sure. But the grit is still there. And the stories all start with some dame walking into a smoky, run-down office.

Who Is This Chandler Guy, Anyway?

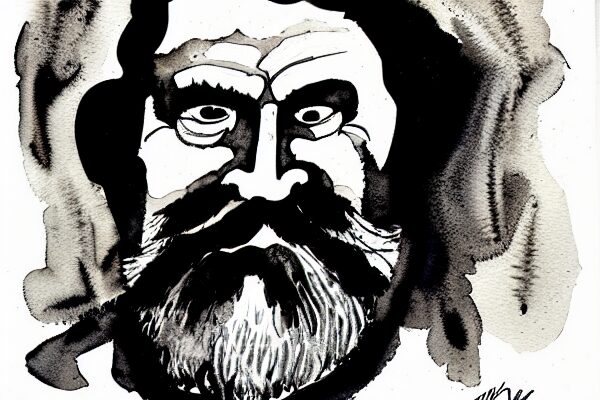

Born in Chicago in 1888, Chandler spent his early years in midwest America before his alcoholic father abandoned their family, after which Chandler’s mother moved them to Ireland so Chandler could get a decent education. He skipped college in favor of traveling around Europe to improve his language skills before returning to Britain to become a civil servant.

The job didn’t suit him, so Chandler found work as a reporter. He might have dedicated himself to becoming a writer at this point, were it not for an encounter with Richard Barham Middleton, author of “The Ghost Ship.” While Chandler admired Middleton, he couldn’t help but notice that Middleton was miserable all the time and eventually committed suicide. “If that guy can’t make it as a writer, what chance do I have?”

He moved back to the U.S. (Los Angeles this time) in 1912 and enlisted in Canada to fight in World War 1. He fought in the trenches of France, which, I’m sure, did nothing to contribute to his mental health problems later in life. When the war was over, he came back and fell in love with a woman who was 18 years his senior. He worked for an oil company before all of his vices caught up with him — the company let him go because of his penchant for booze, women, and skipping work to drink booze with women.

He started writing pulp detective fiction during the great depression as a way of making ends meet. He was influenced by a lot of other crime writers and primarily learned his fiction writing by driving around California reading pulp magazines and feeling bad about himself.

As difficult it is for me to imagine making any money through writing (especially during the Great Depression), it’s easy to see how Chandler’s life contributed to his writing style. Hard-boiled detective fiction is full of no-nonsense characters, sex, violence, and deals primarily with the darker side(s) of society.

Chandler probably felt right at home.

“The Big Sleep,” his first novel, was published in 1939.

Welcome to Grim Reality

Chandler, in an essay for The Atlantic called “The Simple Art of Murder,” had this to say about English mysteries the likes of which were written by Agatha Christie:

There is a very simple statement to be made about all these stories: they do not really come off intellectually as problems, and they do not come off artistically as fiction. They are too contrived, and too little aware of what goes on in the world. They try to be honest, but honesty is an art. The poor writer is dishonest without knowing it, and the fairly good one can be dishonest because he doesn’t know what to be honest about.

If we take literature as a discussion that’s been going on for thousands of years, it seems clear that Chandler is writing in direct response to a handful of other authors; those who wrote detective stories before which “do not come off artistically,” and those stories that are honest.

So, the detective can’t be a prim-and-proper little Belgian who speaks in an odd manner — that’s unrealistic! We need a guy who drinks his breakfast, rattles off one-liners, and risks his life for around $25 a day. Because that’s reality, baby.

What’s more likely is that Chandler took detective stories and injected them with things like sex and pornography and guns and booze because, despite what Chandler himself says, people who like reading about that sort of thing aren’t psychopaths. They’re just people who like excitement in their stories and aren’t necessarily getting it from Poirot or Holmes. Plus, he was following a formula. Editors told him how to put his stories together in a way that they thought would sell, and “The Big Sleep” was essentially just two of those stories put together and padded out to make a novel.

It’s an Absolute Crime

There’s a lot you can learn from “The Big Sleep” and hard-boiled detective fiction in general. One of the biggest and most lasting impacts of this genre has been its effect on prose. The grit, the realism, the short and punchy dialogue. Aside from the language being dated, “The Big Sleep” reads like it could have been written last week rather than in the 30s.

I had a chance to watch the Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall movie from 1946, which seems to put some paint over the grime and soften the story in places. It’s good if you like watching guys hike their pants up over their belly buttons and sweat through their shirts, but otherwise I’d suggest the novel.

The story also popularized “the twist” — not the dance we did last summer, but the idea of a plot that takes sudden and unexpected turns. Again, you have to remember that this story is pretty old, so it’s not like we’re getting M. Night Shamusalan “He Was Dead The Whole Time” sorts of twists, but still.

A Denouement at a Bar With a Double Scotch

Is “The Big Sleep” worth your time? Is anything? It’s hard to tell these days. In a world gone haywire, what are we to make of an unlikely hero, a dedicated shamus who’s too good for this world? Maybe it don’t amount to much, but it sure amounts to three fingers of rye whiskey from a warm bottle.

The answer must be down here somewhere, nestled into the corner of my glass where it kicks up its heels and waits for the next dame to come walking through those doors. When she talks, I know it’ll be a story I’ve heard before, a story I’ve heard a thousand times.

Will I have it in me to hear it again?