While I know that “books” (in the broadest sense) are just a bunch of pages that are put together with glue or string and bound in cloth or leather or human skin or what-have-you, I’ve always found it a little strange to refer to a play as a book. That’s why I find it a bit … surprising that “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” appears as number 11 on the list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die. Woolf isn’t a book. It’s a play.

The difference, to me, is that plays (when they are printed) are missing fundamental information that would be presented in a book. Namely, they lack prose, which is an essential building block of a narrative. Plays are spoken word and minimal direction intended to be performed on a stage. They are purposefully left open to interpretation, with one production being different than another.

This isn’t to say that they aren’t important. It’s easy to see why Edward Albee’s play, first performed in 1962, is significant. But I don’t feel that I fully got it until I’d both read the book and seen a production of the play itself. (Or, in this case, a movie of it.)

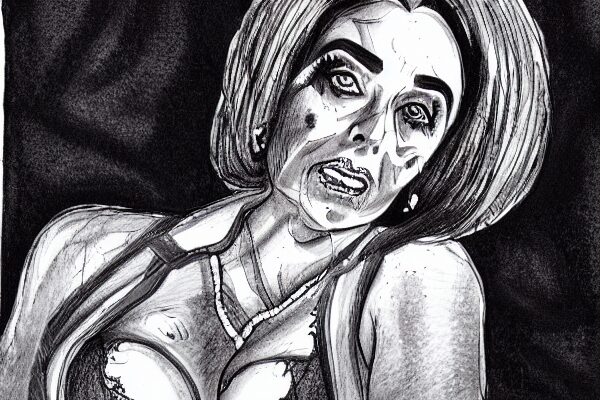

There was a lot of subtle characterization — things like blocking, facial expressions, inflection — that you don’t get from the text. Seeing it performed really makes the thing come alive.

An Absolute Freud

There’s a line in the sand when it comes to being a serious reader of literature, and that line goes by the name LITERARY THEORY. I recognize why many people don’t want to cross that line — some of the most avid readers I’ve ever known have never bothered to concern themselves with LITERARY THEORY and, to be honest, they are happier staying in that particular section of the desert.

Hell, I have a degree in English Writing & Rhetoric and I barely think studying LITERARY THEORY is worth the effort. Those discussions just don’t seem to be happening anymore. Or, more aptly, things have gotten so goddamned fractured that any conversation about LITERARY THEORY lacks a fundamental vernacular.

Harold Bloom is dead and he isn’t coming back.

There are certain works, though, that beg to be viewed through a certain lens, and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” is one of them. It seems to me that Edward Albee was just dying to talk to someone about Freudian Analysis, couldn’t find anybody to chat with, and so wrote a play out of frustration.

Talking about Freudian Analysis is difficult, though. Not only because modern psychology has largely moved on from Freud, but also because nobody understands how or why we should read books utilizing that theory. I dare you, however, to approach “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” without thinking to yourself, “Just what in the hell is wrong with these people?”

The Theatre in Your Head

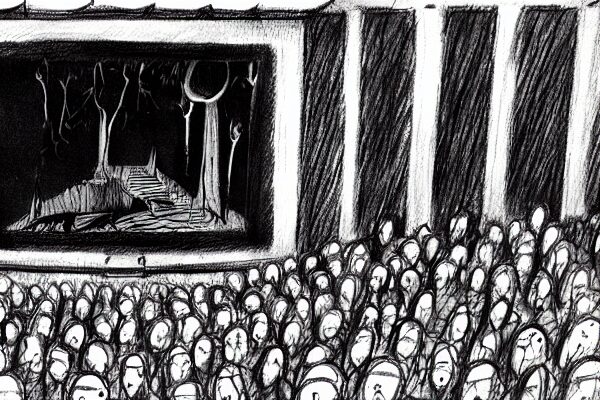

The way I wish I’d had LITERARY THEORY explained to me is this: There’s a theatre in your head and it’s full of all the people you’ve ever met, heard about, or thought you knew. Your parents are in there and so are your siblings. Your teachers are in there along with your friends, coworkers, and neighbors.

They see everything you see and read everything you read. It appears as if on a screen before them, and they sit comfortably munching on popcorn and slurping diet soda while enjoying the show.

Every now and then, you come across a movie or TV show or a book and you think, “By golly, Dad would love this.” You think so because you have a clear understanding of good ol’ Dad and you know what would turn his crank. In your head, that little version of your father stands up in the theatre and cheers.

“Bravo!” he cries.

Alternatively, sometimes you see something Dad would hate, and your little head-pappy starts throwing ice cubes at the screen.

“Filth!” he roars as a little version of your mom tells him to pipe down and grips his leg so tight her nails almost cut him.

“Typical,” your brother mumbles.

LITERARY THEORY is just a way of thinking about how certain groups of people would respond to whatever you’re reading. You try to see a work through the eyes of somebody else, respond to it the way the would respond to it, etc.

So, when we say we’re going to consider “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” through the lens of Freudian Literary Theory, all we mean is that we’re reading the book as if there’s a little psychoanalyst sitting in our head-theatre chiming in about what we’re reading.

A Night of Fun and Games

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” features four characters. There’s George (a college professor) and Martha (the Dean’s daughter), an older married couple, who have invited Nick and Honey over to their house for drinks late one night after a faculty mixer. The only problem seems to be that George and Martha are both certifiable (in a literal sense) and are intent upon tormenting each other for their perceived failures and shortcomings. Every quip in the fast-paced dialogue is a barb meant to incite a drastic response as George and Martha use the younger married couple in their attempts to humiliate one another.

They think of this torment, which seemingly happens with great regularity, as a kind of “game” that they play. While the torment is real and both George and Martha say things that are so abysmally cruel, this is all just part of who they are. They’ve been doing it for quite some time, and they don’t show signs of stopping.

One of them leaving the other would be an easy, sure-fire way to fix their problems, but that seems to be against the rules of the game.

Do they really love each other? That’s up for debate. But they are dedicated, and often that is enough.

The four lunatics drink and drink and drink the night away and readers are left feeling second-hand embarrassment as George taunts Martha and Martha taunts George. Some of the scenes are just so goddamned uncomfortable that it strains believability. Right around the time George tells Nick that he thinks Honey is “slim-hipped” is when Nick and/or Honey should have just gone home.

But for some reason they don’t. Even when Martha starts grinding on Nick and George just sits there pretending it doesn’t bother him. (It can’t bother him, don’t you see! He’d lose the game if it bothered him.)

Eventually, the sources of their psychological trauma are revealed and we begin to see a picture of why they’re doing what they’re doing. I won’t spoil it for you, because it is a fairly good twist, but astute readers will see it coming.

The Freudian Slip

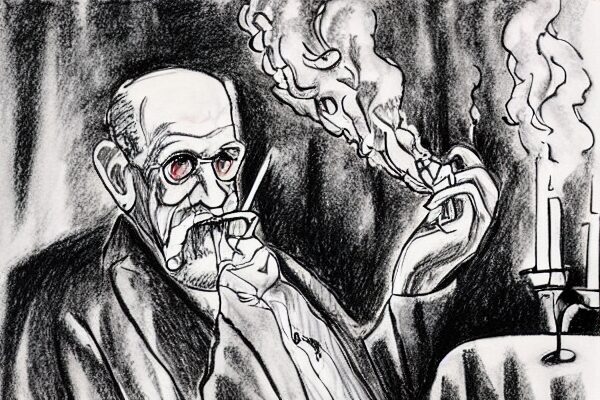

As to why this play begs to be read through the lens of Freudian Literary Analysis has to do with several of the elements of psychoanalysis. There are themes and imagery of repressed memories and the unconscious mind. There’s the Uncanny, and the mother (ba-dop CHING!) of Oedipal Complexes. The play oozes sexuality at several points and readers can’t help but see themselves within the characters and begin to psychoanalyze themselves in the process.

Essentially, a little Sigmund Freud sits in your head-theatre in a smoking jacket and mumbling, “What is wrong with these people? Is it a symptom of a broader psychological malady that has infected the whole of 1960’s America? Or, perhaps, is it representative of our own inner desires to murder our fathers?”

Then everyone else shushes him and demands that he puts out his goddamned pipe. “You can see Liz Taylor’s cleavage!” your dad stage whispers.

All in All

People in the 1960’s were nuts for psychoanalysis and seemingly thought we were somehow going to unlock the mysteries of the mind by carefully analyzing the way people speak and act. Edward Albee thought about it so hard he gave himself fits. And while there might be some elements of truth to it, as much as we might wish we could understand why we’re all so messed up, Nick and Honey would have left that shitty party as soon as they got there. Liz Taylor or no Liz Taylor, it was an awful party, and that schtick with the umbrella gun was a straight up dick move. Nobody would stick around to receive such abuse, and even if they did, there would have been more punches or at least some biting.

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is worth checking out, but, if you read it, you’ll run the risk of starting to psychoanalyze yourself and that’s a fool’s gambit. Only suckers try to therapize themselves.

Did I say that?

Anyway, you can read the whole thing in an hour, which ain’t bad.