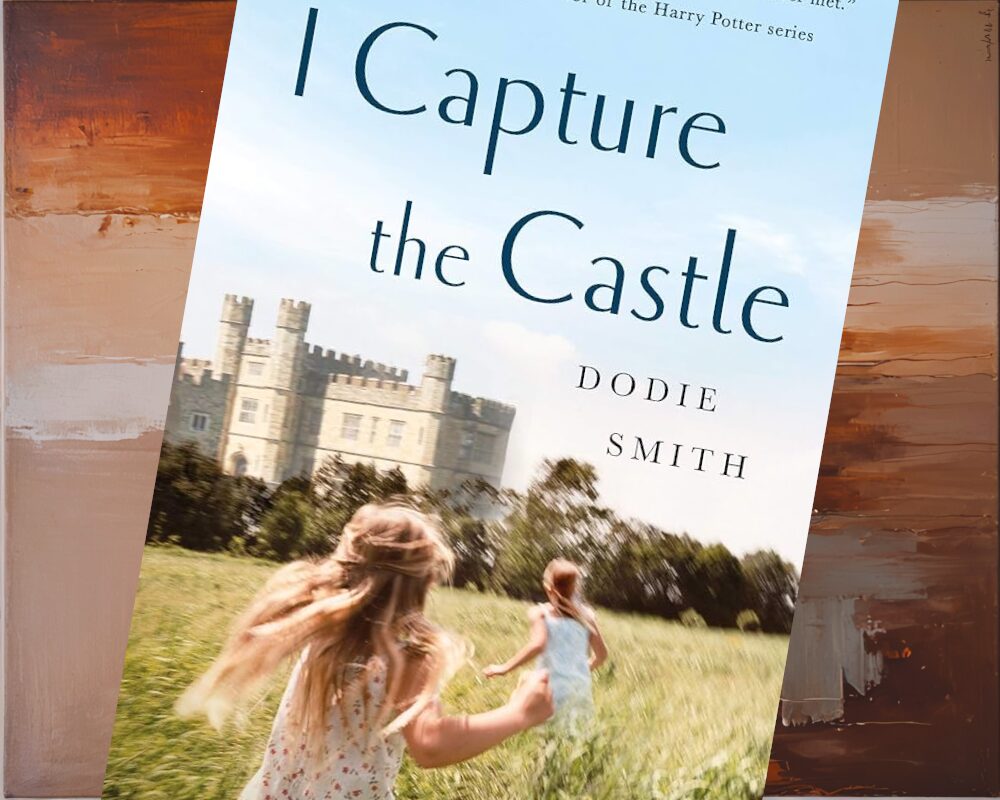

At the start of a project such as this — tackling a list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die — “I Capture the Castle” by Dodie Smith (#837) is exactly the sort of book you hope to come across. It isn’t a heavy story in any sense of the word (which makes it a bit of an odd duck on a list that includes the Bible), but it has enough charm, wit, and humor to justify its place on anybody’s list of favorites.

I found the book when I was randomly browsing the shelves at Barnes & Noble. What I sometimes do is pick a random number between 1 and 1,000, find the corresponding book and author on the list, and go see if that author has any works on the shelves. It’s essentially a little game of Deal or No Deal, except the result is usually me trudging through a bookstore mumbling something akin to, “How do you not have a copy of Slaughterhouse Five? What kind of SOCIETY are we living in?”

“I Capture the Castle” by Dodie Smith was there, though, and a cursory glance through the first few pages told me it would probably be a book I enjoy.

It was, and during a very stressful week, if Cassandra Mortmain’s quirky little diary wasn’t exactly a balm to sooth my bitter soul, then it was certainly warming. Like soup, or a bath. Or soup in the bath. (Do you suppose anyone ever eats soup in the bath? It might be fun, but what if you spill?)

This is the Story of a Girl

The story of “I Capture the Castle” follows Cassandra and her family, who are poor and yet somehow live in a castle. (Go figure.) Her father had been a promising novelist before discovering that he maybe only had one good book in him, and yet, despite not having two pennies to rub together, nobody in the household bothers to get a day job. Why? Reasons.

So, they eat cheese and biscuits and other mousy finger foods while sitting in the sink and being quirky at one another. Cassandra watches everything that goes on and journals about it, being both intelligent and daft in equal measure, while their mother-in-law dances around naked and their father reads detective novels.

When the owner of the castle (Cassandra’s family just rents it) dies and it turns out that the heirs to the estate are a couple of young, single men, romance and drama ensue. Does Cassandra fall in love with one of these new guys, or does, perhaps, her sister Rose? What of Stephen, the handsome gardner, who not-so-subtly dotes on Cassandra at every opportunity (and is one of the only people who actually works for a living)? Will he fall in love with one of the girls?

I heard the book referred to as “Austen and Brontë fan fiction,” and it’s hard to disagree. It hits a lot of the same notes, but, having been published in 1948, with more a modern (sense and) sensibility. Young women going to parties, wondering who they’re going to marry, are they in love, yes maybe, but possibly not, and oh we’re so poor if we marry one of these young men we’ll finally have money, but is that right, is it okay to marry someone if you aren’t head-over-heels nuts for them, and what to do about Stephen, he’s like a brother, isn’t he, and what does “love” even mean? Won’t someone tell us? *Swoon*

And it works because, well, it works. Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters know how to spin a yarn, and if you use them as your jumping-off point, odds are you’re going to land somewhere close to the mark.

Telling Tales out of School

I feel similarly toward “I Capture the Castle” as I feel toward another book I recently read — “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” That might seem like a strange comparison, but my point is that both books scratch a particular itch: Instead of trying to plumb the depths of the human psyche, they’re just interesting stories that are supposed to be fun to read.

It’s a matter of reader engagement, or perhaps you might call it readability. You get the impression that Dodie Smith really liked a good story, thought Jane Austen was just the tops, and wanted to make a top story of her own. So, BAM, she wrote this. And while there are certainly themes in Castle that are worth exploring, it’s seems clear that her approach was to make something that was entertaining.

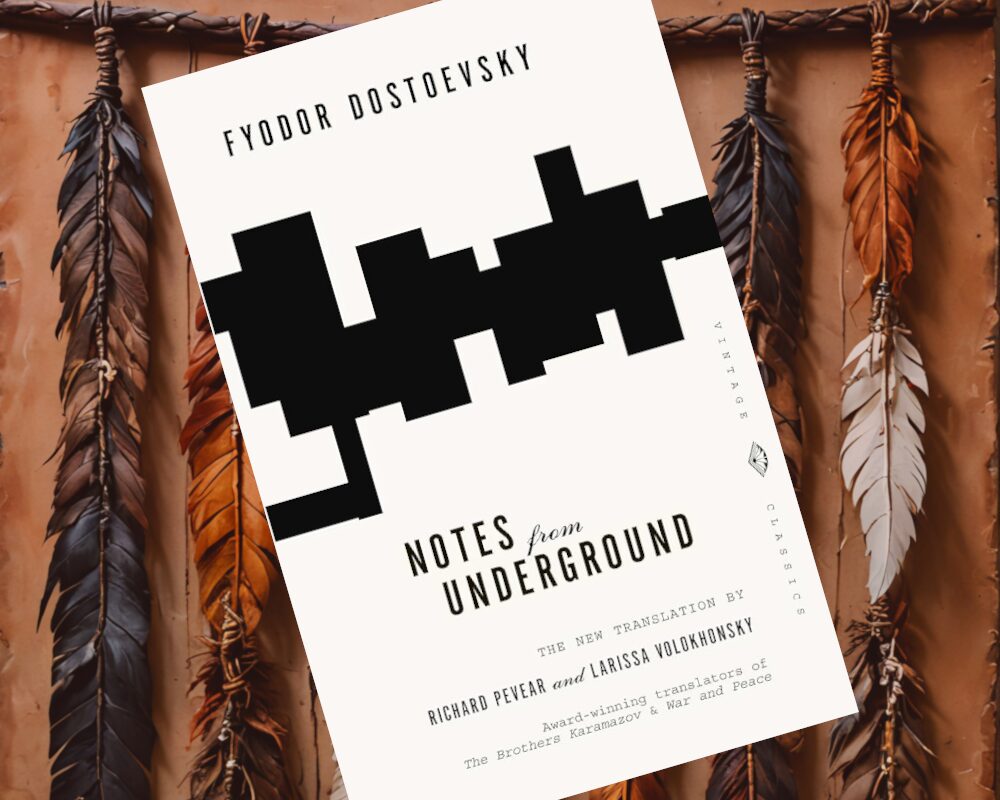

That’s not how everyone approaches fiction, as my recent forays into Dostoevsky and Woolf can verify. A lot of modernists are that way — story is secondary to style — but those modernists were reacting to authors that Dodie Smith tried to emulate.

Dodie Smith read “Pride and Prejudice” and went, “Neat!”

Virginia Woolf read it and went, “Eat SHIT Jane Austen that’s not how people really think!”

Both are valid responses.

Still, it’s always seemed a little…pointless to write a book that people aren’t going to enjoy the process of reading. Books that critics say are meant to “challenge readers’ perceptions” about various things, books with disjointed styles or syntax that’s difficult to parse or that are written in the second person.

(In a panic, I just went and checked if “The Naked Lunch” was on the list of 1,000 Books. It isn’t, thank God.)

I Capture Your Pawn

What people will remember and appreciate most about “I Capture the Castle” is probably its writing, which eloquently captures a mixture of melancholy and humor in way that makes you go, “Awwww,” at least once per chapter. You recognize how sad everything is, but at the same time Cassandra writes about it so well that you don’t mind all the gloom. That’s not an easy balance to strike.

The setting — the titular “castle” that is “captured” in Cassandra’s prose — is interesting, and the book does raise issues of class and gender, but the point is never to hit you over the head with it. The plot moves at a steady pace and there are enough turns that you never fully get a handle on what’s going to happen. Endings, in these sorts of stories, are a big deal.

For a work that tries to emulate the romance of an Austen novel, the ending is surprisingly satisfying. (I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I don’t mind spoilers one bit — I usually read the end of a book first, just to see how things are going to “end up” — but I recognize that the rest of you yahoos give a hoot, so I won’t spoil it for you.) I’ll just say that’s it’s unlikely you’ll guess who ends up with whom.

I’ll also say that “I Capture the Castle” by Dodie Smith is utterly worth your time, especially if you’ve read your classics and haven’t been able to get your 19th Century Romance fix in a while. It’ll certainly…capture your attention.

* * *

The 2003 movie adaptation isn’t terrible and is on YouTube right now.